G.B. - Invasion of England, 1066

Invasion of England, 1066

King Edward of England (called "The Confessor" because of his construction of Westminster Abbey) died on January 5, 1066, after a reign of 23 years. Leaving no heirs, Edward's passing ignited a three-way rivalry for the crown that culminated in the Battle of Hastings and the destruction of the Anglo-Saxon rule of England.

The leading pretender was Harold Godwinson, the second most powerful man in England and an advisor to Edward. Harold and Edward became brothers-in-law when the king married Harold's sister. Harold's powerful position, his relationship to Edward and his esteem among his peers made him a logical successor to the throne. His claim was strengthened when the dying Edward supposedly uttered "Into Harold's hands I commit my Kingdom." With this kingly endorsement, the Witan (the council of royal advisors) unanimously selected Harold as King. His coronation took place the same day as Edward's burial. With the placing of the crown on his head, Harold's troubles began.

Across the English Channel, William, Duke of Normandy, also laid claim to the English throne. William justified his claim through his blood relationship with Edward (they were distant cousins) and by stating that some years earlier, Edward had designated him as his successor. To compound the issue, William asserted that the message in which Edward anointed him as the next King of England had been carried to him in 1064 by none other than Harold himself. In addition, (according to William) Harold had sworn on the relics of a martyred saint that he would support William's right to the throne. From William's perspective, when Harold donned the Crown he not only defied the wishes of Edward but had violated a sacred oath. He immediately prepared to invade England and destroy the upstart Harold. Harold's violation of his sacred oath enabled William to secure the support of the Pope who promptly excommunicated Harold, consigning him and his supporters to an eternity in Hell.

The third rival for the throne was Harald Hardrada, King of Norway. His justification was even more tenuous than William's. Hardrada ruled Norway jointly with his nephew Mangus until 1047 when Mangus conveniently died. Earlier (1042), Mangus had cut a deal with Harthacut the Danish ruler of England. Since neither ruler had a male heir, both promised their kingdom to the other in the event of his death. Harthacut died but Mangus was unable to follow up on his claim to the English throne because he was too busy battling for the rule of Denmark. Edward became the Anglo-Saxon ruler of England. Now with Mangus and Edward dead, Hardrada asserted that he, as Mangus's heir, was the rightful ruler of England. When he heard of Harold's coronation, Hardrada immediately prepared to invade England and crush the upstart.

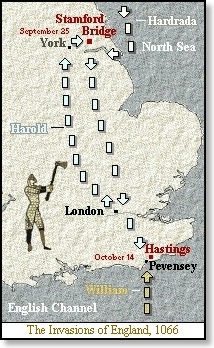

Hardrada of Norway struck first. In mid September, Hardrada's invasion force landed on the Northern English coast, sacked a few coastal villages and headed towards the city of York. Hardrada was joined in his effort by Tostig, King Harold's nere-do-well brother. The Viking army overwhelmed an English force blocking the York road and captured the city. In London, news of the invasion sent King Harold hurriedly north at the head of his army picking up reinforcements along the way. The speed of Harold's forced march allowed him to surprise Hardrada's army on September 25, as it camped at Stamford Bridge outside York. A fierce battle followed. Hand to hand combat ebbed and flowed across the bridge. Finally the Norsemen's line broke and the real slaughter began. Hardrada fell and then the King's brother, Tostig. What remained of the Viking army fled to their ships. So devastating was the Viking defeat that only 24 of the invasion force's original 240 ships made the trip back home. Resting after his victory, Harold received word of William's landing near Hastings.

Construction of the Norman invasion fleet had been completed in July and all was ready for the Channel crossing. Unfortunately, William's ships could not penetrate an uncooperative north wind and for six weeks he languished on the Norman shore. Finally, on September 27, after parading the relics of St. Valery at the water's edge, the winds shifted to the south and the fleet set sail. The Normans made landfall on the English coast near Pevensey and marched to Hastings.

Harold rushed his army south and planted his battle standards atop a knoll some five miles from Hastings. During the early morning of the next day, October 14, Harold's army watched as a long column of Norman warriors marched to the base of the hill and formed a battle line. Separated by a few hundred yards, the lines of the two armies traded taunts and insults. At a signal, the Norman archers took their position at the front of the line. The English at the top of the hill responded by raising their shields above their heads forming a shield-wall to protect them from the rain of arrows. The battle was joined.

The English fought defensively while the Normans infantry and cavalry repeatedly charged their shield-wall. As the combat slogged on for the better part of the day, the battle's outcome was in question. Finally, as evening approached, the English line gave way and the Normans rushed their enemy with a vengeance. King Harold fell as did the majority of the Saxon aristocracy. William's victory was complete. On Christmas day 1066, William was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey.

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry (actually an embroidery measuring over 230 feet long and 20 inches wide) describes the Norman invasion of England and the events that led up to it. It is believed that the Tapestry was commissioned by Bishop Odo, bishop of Bayeux and the half-brother of William the Conqueror. The Tapestry contains hundreds of images divided into scenes each describing a particular event. The scenes are joined into a linear sequence allowing the viewer to "read" the entire story starting with the first scene and progressing to the last. The Tapestry would probably have been displayed in a church for public view.

History is written by the victors and the Tapestry is above all a Norman document. In a time when the vast majority of the population was illiterate, the Tapestry's images were designed to tell the story of the conquest of England from the Norman perspective. It focuses on the story of William, making no mention of Hardrada of Norway nor of Harold's victory at Stamford Bridge. The following are some excerpts taken from this extraordinary document.

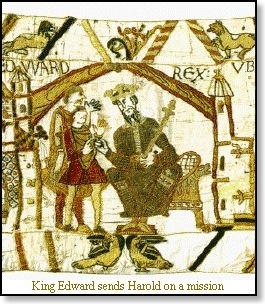

King Edward sends Harold on a Mission

The Tapestry's story begins in 1064. King Edward, who has no heirs, has decided that William of Normandy will succeed him. Having made his decision; Edward calls upon Harold to deliver the message.

This at any rate, is the Norman interpretation of events for King Edward's selection of William is critical to the legitimacy of William's later claim to the English crown. It is also important that Harold deliver the message, as the tapestry explains in later scenes.

In this scene King Edward leans forward entrusting Harold with his message. Harold immediately sets out on his fateful journey.

Harold Swears an Oath to William

Pursuing his mission, the Tapestry describes how Harold crosses the English Channel to Normandy, is held hostage by a Norman count and is finally rescued by William.

Harold ends up in William's castle at Bayeux on the Norman coast where he supposedly delivers the message from King Edward. At this point the Tapestry describes a critical event. Having received the message that Edward has anointed him as his successor; William calls upon Harold to swear an oath of allegiance to him and to his right to the throne. The Tapestry shows Harold, both hands placed upon religious relics enclosed in two shrines, swearing his oath as William looks on. The onlookers, including William, point to the event to add further emphasis. One observer (far right) places his hand over his heart to underscore the sacredness of Harold's action. Although William is seated, he appears larger in size than Harold. The disproportion emphasizes Harold's inferior status to William. The Latin inscription reads "Where Harold took an oath to Duke William."

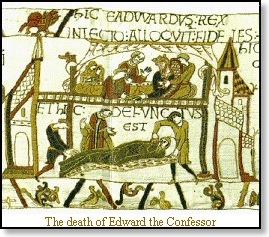

The Death and Burial of Edward the Confessor

The Tapestry describes Harold's return to England after swearing his oath to William and his report to King Edward. The story then advances forward two years to 1066 and the death of Edward.

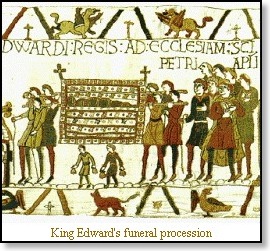

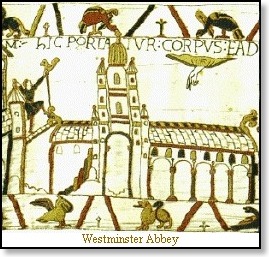

The death and burial of King Edward is presented in three scenes whose chronological order is reversed. The first image (1) depicts Westminster Abbey. This is followed by Edward's funeral procession (2) and then his death (3).

The Death of Edward

In this scene (3) Edward is presented as both alive and dead. In the top portion of the panel Edward converses with those gathered at his bedside. The Latin inscription reads "Here King Edward addresses his faithful ones." At the foot of his bed sits Edward's wife who is also Harold's sister. At the side of the bed stands Stigand, the archbishop of Canterbury who performs a religious ceremony. The dying king addresses Harold who kneels in front of him. It is here that Edward supposedly anointed Harold as his successor giving legitimacy to Harold's claim to the crown.

In the lower panel Edward is prepared for burial. The bishop performs last rites while the embalmers go about their work. The Latin inscription reads "And here he died."

The Procession

Edwards' body, wrapped in linen, is carried to the church for burial (2). The Latin inscription reads "Here the body of King Edward is carried to the Church of St. Peter the Apostle." Edward's burial took place on January 6, 1066.

In its entry for the year 1066, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes Edward's death as follows: "In this year was consecrated the minster at Westminster, on Childer-mass-day. And King Edward died on the eve of Twelfth-day; and he was buried on Twelfth-day within the newly consecrated church at Westminster. And Harold the earl succeeded to the kingdom of England, even as the king had granted it to him, and men also had chosen him thereto; and he was crowned as king on Twelfth-day."

Westminster Abbey

Edward's funeral procession completes its journey at Westminster Abbey (1). King Edward began work on the abbey in 1050 and construction was completed shortly before his death. The pious Edward was awarded the distinction "the Confessor" for his effort. Unfortunately, the King fell ill on Christmas eve and was unable to attend the abbey's consecration.

The Tapestry conveys the newness of the abbey by the workman affixing the weather vane atop the roof to the left. God's blessing upon the consecrated structure is represented by the hand appearing from the clouds above.

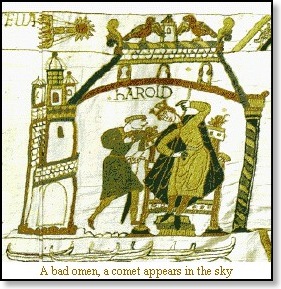

A Bad Omen: the Appearance of Halley's Comet

Harold is crowned king on January 6. In the spring, near Easter, a comet appears in the sky. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the event: "Easter was then on the sixteenth day before the calends of May. Then was over all England such a token seen as no man ever saw before. Some men said that it was the comet-star, which others denominate the long-hair'd star. It appeared first on the eve called 'Litania major', that is, on the eighth before the calends of May; and so shone all the week."

We now know that the comet-star in the sky was Halley's Comet making one of its 76-year cyclical appearances. In the Tapestry, an attendant rushes to tell Harold of the celestial happening as he sits upon his throne. The comet appears at the upper left. The portrayal acquires a sense of foreboding as empty long boats appear below the scene. These no doubt presage the invasion fleet William will employ to cross the Channel. The Tapestry implies that the appearance of the comet expresses God's wrath at Harold for breaking his oath to William and assuming the throne. Retribution will be found in the invasion fleet.

William Launches His Invasion

Upon hearing the news of Harold's coronation, William immediately orders the building of an invasion fleet. The Tapestry describes in detail the construction of the fleet and preparations for the invasion providing insight into eleventh century building techniques. With preparations complete, William waits on the Normandy shore for a favorable wind to take him to England.

The favorable wind arrives on September 27, and the fleet sets sail, its ships loaded with knights, archers, infantry, horses and the lumber necessary to build two or three forts. This scene shows William's ship as the fleet approaches Pevensy on the English shore. A cross adorns the top of the ship's mast. Below the cross, a lantern guides the way for the rest of the fleet. Shields line the ship's gunwales, reminiscent of the practice of the Norman's Viking ancestors. A dragon's head sits on the ship's prow and a bugler blows his horn at the ship's stern. A ship laden with horses sails along side William's craft. The fleet lands on September 28 and the invasion army makes its way to Hastings.

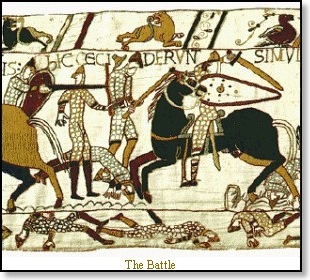

The Battle

This is one of many scenes depicting the ferocity of the battle. Wielding his battle-axe, a Saxon deals a death-blow to the horse of a Norman. This was the first time the Normans had encountered an enemy armed with the battle-axe. For the Saxons, this was the first time they had battled an enemy mounted on horseback. This scene probably describes the later stages of the battle when the Norman knights had broken through the Saxon shield wall. At the bottom of the scene lay the dead bodies of both Normans and Saxons.

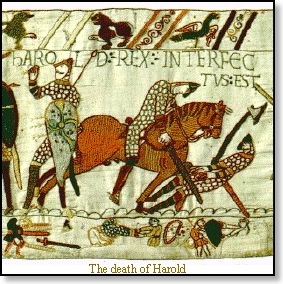

The Death of Harold

King Harold tries to pull an arrow from his right eye. Several arrows are lodged in his shield showing he was in the thick of the battle. To the right, a Norman knight cuts down the wounded king assuring his death. At the bottom of the scene the victorious Normans claim the spoils of war as they strip the chain mail from bodies while collecting shields and swords from the dead. Scholars debate the meaning of this scene, some saying that the man slain by the knight is not Harold, others contesting that the man with the arrow wound is not Harold, others claiming that both represent Harold. The Latin inscription reads "Here King Harold was killed." The Tapestry ends its story after the death of Harold.

William ruled England until his death in 1087. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recalls the Norman King in its entry for that year: "But amongst other things is not to be forgotten that good peace that he made in this land; so that a man of any account might go over his kingdom unhurt with his bosom full of gold. No man durst slay another, had he never so much evil done to the other; and if any churl lay with a woman against her will, he soon lost the limb that he played with. He truly reigned over England; and by his capacity so thoroughly surveyed it, that there was not a hide of land in England that he wist not who had it, or what it was worth, and afterwards set it down in his book."

References:

Bernstein, David, The Mystery of the Bayeux Tapestry (1987); Howarth, David, 1066 the Year of the Conquest (1978); Ingram, James (translator), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (1823); Wood, Michael, In Search of the Dark Ages (1987).

Resources on the Web:

Battle of Hastings, 1066

Bayeux Tapestry

![]()